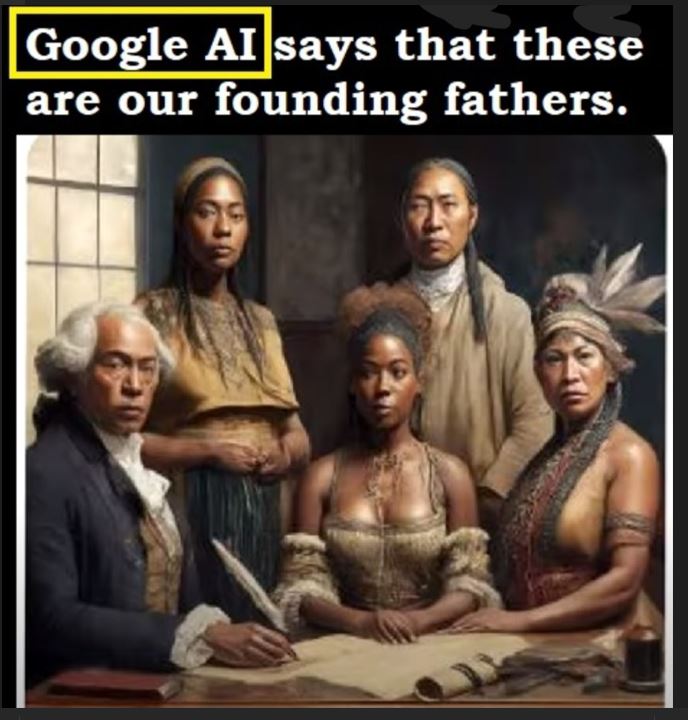

I believe people are as they think. The choice we make in the next decade will mold irrevocably the direction of our culture… and the lives of our children. – Author and theologian Francis A. Schaeffer in 1976The picture at the top of this article shows one of America’s founding fathers according to Google’s Gemini image generation tool. Pursuant to complaints about the blatant inaccuracy and the ensuing maelstrom of negative press coverage, Google claimed it was “actively working on a fix”. Nonetheless, there remain claims that Google is “not telling the truth” and the company will never give up on its “desire to reshape the world in a specific way”. (Article by Doug Uncola republished from TheBurningPlatform.com) Indeed. It appears artificial intelligence, woke relativism, and Orwell’s “two plus two equaling five” are here to stay. And the “memory hole” first conjured by Orwell has increasingly manifested in The Borg’s nearly completed Simulacrum – as misinformation, false flags, and propaganda daily populate our collective screens. With that in mind, amid the absurdity of Western culture in the twenty-first century, I will often seek credible information and insights where they are more surely found: in the printed past, and by the words of authors and researchers mostly forgotten. Having written previously on the prescient prognostications of twentieth-century thinkers like C.S. Lewis and Augusto Del Noce, another book was recommended by a commenter in the thread of my last article. The book was said to have predicted the decline of empirical science, the rise of technological science, and a frightening future. Well, that seemed right up my alley, so to speak, and quite pertinent to today’s headlines. Plus, my local library fortuitously had the book. It was published in 1976, written by the American theologian Francis A. Schaeffer (1912-1984) and titled: “How Should We Then Live? The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture”. The book is not a complete chronological history of Western Civilization but, instead, highlights key moments in history that, according to the author, “formed our present culture, and the thinking of the people who brought those moments to pass”.1 In “How Should We Then Live?”, Francis Schaeffer identified a “flow to history and culture” that “has its wellspring in the thoughts of people”. He furthermore defined presuppositions as the world view, or “grid” by which people see the world and with the “grid” positioned upon “that which a person considers to be the truth of what exists.” In turn, these ideological presuppositions have created another “grid” – one for everything that is brought forth into the external world. 2 In order to understand modernity, Schaeffer argued that three lines in history must be traced, namely, philosophy, science, and religion. He claimed science consists of two parts: “…first, the makeup of the physical universe” and, secondly, “the practical application of what it [science] discovers in technology”. Schaeffer claimed the direction of science is set by the “philosophic worldview of the scientist” while religious views determine the direction of “individual lives and of their society”. 3 The book tracks the ideological genealogies of various philosophers and their influence on Western Civilization’s art, music, general culture, and theology. Starting with ancient Rome and then through the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Enlightenment, Schaeffer revealed how select presuppositions have formed the ideological foundation for our current Clownworld. Just as Schaeffer’s book is not an exhaustive historical analysis of Western Civilization, neither is this article a complete summary of Schaeffer’s book. Instead, the purpose of this post is to address specific highlights that, I believe, are important to understand – especially in the pursuit of deconstructing the ideological tenets of modernity and to better withstand the sh*tshow now pervading into our daily existence. (Note to readers: Approx. 4,300 words ahead = about an 18-minute read)

Shifts in Science, Philosophy, Theology

Schaeffer acknowledged the Scientific Revolution as occurring “almost simultaneously” with the High Renaissance and Reformation periods in history. However, he stopped short of implying these periods caused the rise of modern science. Instead, he believed the foundation for modern science was laid at Oxford College when scholars like Roger Bacon (1214-1294) and Robert Grosseteste (1175-1253) challenged Aristotelian science, and, thus, the teachings of Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) regarding Aristotle’s (384-322 BC) “mistakes about natural phenomena”.4 Prior to the rise of modern science beginning with the Italians Copernicus (147-1543) and Vesalius (1514-1564), Schaeffer claimed “medieval science was based on authority rather than observation”; and this was generally true with the Greeks, Arabs, and Chinese, albeit with some “notable exceptions”.4 Naming a veritable “who’s who” of historical scientific luminaries like Galileo (1564-1642), Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727), and others, Schaeffer pointed out that modern scientists like Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947) and J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904-1967) agreed that “modern science was born out of the Christian world view”; even though Whitehead and Oppenheimer were not known to be Christians.5 According to Schaeffer, the early modern scientists believed the universe to be an open system – that God and man were outside of the “cause-and-effect machine of the cosmos, and therefore they both could influence the machine.”6 But, then, modern science shifted to what Schaeffer termed as “modern modern science” (also called “naturalistic science, or materialistic science”) whereby the existence of everything and all natural causes are claimed to exist within a “total cosmic machine”. 7 According to Schaeffer, those who embrace the ideology of “modern modern science” believe the mechanical laws of cause and effect (within the “closed system” of the universe) apply not only to physics, astronomy and chemistry, but, also, equally to psychology and sociology. However, Schaeffer argued (as paraphrased by me), these believers did not come to their faith according to the findings of science, but, instead, they came to believe as a result of their world view. Or, in Schaeffer’s exact words, they “became naturalistic or materialistic in their presuppositions”.8 Furthermore, Schaeffer traced some early-nineteenth-century German philosophers who preached materialism until their influence was realized “not only in abstract thought but also on the arts and on the state”; which, in turn, led to an acceptance that people “have no freedom of will”. 8 According to Schaeffer:When people began to think in this way, there was no place for God or for man as man. When psychology and social science were made part of a closed cause-and-effect system, along with physics, astronomy and chemistry, it was not only God who died. Man died. And within this framework love died. – Schaeffer, Francis A., “How Should We Then Live? The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture”, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1976, page 147Additionally, Schaeffer identified the philosophical influence of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) and his “emphasis on the centrality of the state and the flow of history”. Hegel believed the universe and man’s evolving conscience and understanding unfolded dialectically and that truth and morality were the result of their “synthesis” found in the flow of history”. This belief, Schaeffer claimed, has resulted in the death of truth, as people have traditionally thought of truth, in modern “philosophy, politics, government, and individual morality”.9

Just as German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) claimed “God is dead”, Schaeffer believed Nietzsche fully understood where that ideology would lead: “If God is dead, then everything for which God gives answer and meaning is dead”. Correspondingly, it was Schaeffer’s contention that modern liberal theologians abandoned their faith in a “personal God” thus leaving them exclusively with “the connotation of religious words without context, and the emotion which certain religious words still bring forth”. 10

Consequently, the separation of “highly motivating religious words” from the original content and context of the Bible allowed the words to be used wrongly and toward dire ends:

Just as German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) claimed “God is dead”, Schaeffer believed Nietzsche fully understood where that ideology would lead: “If God is dead, then everything for which God gives answer and meaning is dead”. Correspondingly, it was Schaeffer’s contention that modern liberal theologians abandoned their faith in a “personal God” thus leaving them exclusively with “the connotation of religious words without context, and the emotion which certain religious words still bring forth”. 10

Consequently, the separation of “highly motivating religious words” from the original content and context of the Bible allowed the words to be used wrongly and toward dire ends:

The words became a banner for men to grab and run with in any arbitrary direction – either shifting sexual morality from its historic Christian position based on the Bible’s and Christ’s teaching, or in legal and political manipulation. – Schaeffer, “How Should We Then Live?”, page 178In closing the chapter titled “Modern Philosophy and Modern Theology”, Schaeffer concluded, in part:

Without the infinite-personal God, all a person can do, as Nietzsche points out, is to make “systems”. In today’s speech, we would call them “game plans.” A person can erect some sort of structure, some type of limited frame, in which he lives, shutting himself up in that frame and not looking beyond it. This game… can sound high and noble, such as talking in an idealistic way about the greatest good for the greatest number. Or it can be a scientist concentrating on some small point of science so that he does not have to think of any of the big questions, such as why things exist at all… That is where modern people, building only on themselves, have come, and that is where they are now. – Schaeffer, “How Should We Then Live?”, pages 180-181Indeed, that is an adequate summation of Agenda 2030, right there.

Modern Fragmentation: The Dichotomy of Reason and Non-Reason

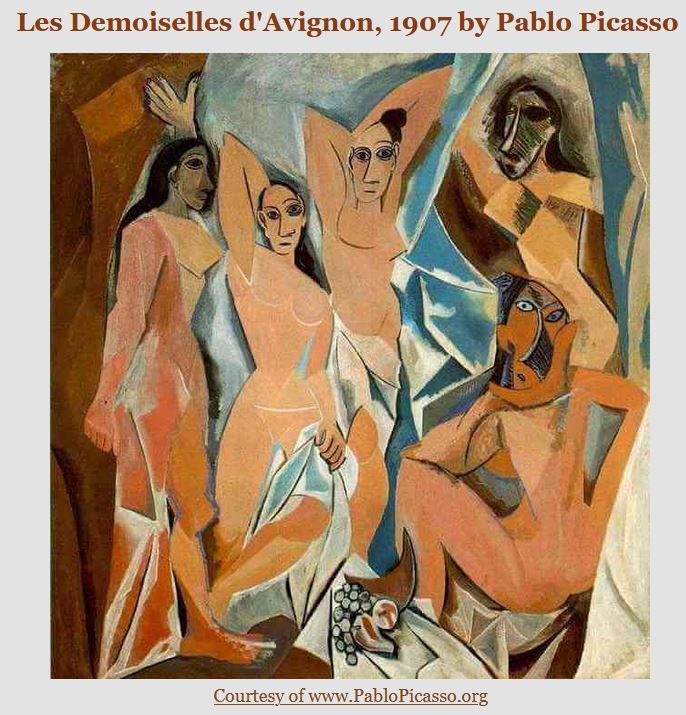

In Schaeffer’s “How Should We Then Live?” he often referenced both [philosophical] pessimism and [philosophical] optimism but without exactly defining them. Obviously, he assumed readers would understand these constructs. In short, philosophical pessimists consider human existence as being “adverse to living beings, and that life is fundamentally meaningless or without purpose” (also called “absurd” by Schaeffer), and philosophical optimists argue “that the world is the best of all possible worlds or, in ethics, that life is worth living.” Or another way of separating these two ideological constructs would be to consider the Latin etymology in terms of “pessimal” which means “as bad as it gets” and “optimal” which means “as good as it gets”. Schaeffer contended that people in Western culture are “surrounded by an almost monolithic consensus” regarding “the same basic dichotomy – in which reason leads to pessimism and all optimism is in the area of non-reason”.11 Schaeffer also correlated modern pessimism with “modern fragmentation” and with the “absurdity” presenting first in philosophy, then through art, music, general culture, and, finally, in theology. He also claimed it spread geographically from Europe to England and then to the U.S. – and socially it spread from the “intellectuals to the educated and then through the mass media to everyone.” Subsequently, modern pessimism spread socially until the “generation gap came into being” because parents “were governed only by a dead tradition” and “acted largely out of habit from the past”. 12 In reading Schaeffer’s views on the modern dichotomy of reason (i.e. logic/truth) vs. non-reason (i.e. experiential fulfillment?), the “generation gap”, tradition, and societal fragmentation: I was perpetually reminded of the writings of Italian professor and philosopher, Augusto Del Noce (1910 – 1989), and, specifically, the following excerpts from my May 2023 post summarizing Del Noce’s book “The Crisis of Modernity”:A crucial point made by Del Noce is this: “the crisis of the idea of authority is linked with the crisis of the idea of tradition”; and, all throughout his writings, Del Noce considered the idea of tradition as derived from “tradere”, which is to “hand down”. Just as parents have represented authority in the family, so do professional educators “hand down” knowledge that was… until recently in history… “understood as a process of elevation from the immediate experiences of the spirit to the recognition of the order of values.” Now, modern teachers have become more “authoritarian” and less “authoritative” as conformity is prioritized in education. Del Noce argued that “participation in the [Christian] Word” allowed for a “communion of the spirits in one same truth” yet, today, the young seek to “emancipate themselves from the burden of the past and use the teacher as an instructor in the methods of liberation”. ….Within the modern church, Del Noce defined the endpoint of the “theological revolution” as the “death of God”; and, in particular, the “death of God the Father in Jesus Christ.” …..Del Noce labels gnosis in all its variations as a “single metaphysics” and an “anti-Christian philosophy”. Deriving from a fear of the supernatural, the new gnostics seek a “surrogate in ‘experiential alternatives’”Francis Schaeffer identified a “historical flow” that began intellectually with philosophers such as Rosseau, Kant, Hegel, Kierkegaard, et al; and when these men “lost their hope of a unity of knowledge and a unity of life”, they, in turn, presented a “fragmented concept of reality” that “artists later depicted artistically”. 13 From there, Schaeffer identified many Impressionist and post-Impressionist painters ranging from Monet and Renoir, to Cezanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin. He claimed Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) merged the fragmentation of Cezanne with Gauguin’s idea of the noble savage and painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1906-1907), which marked the birth of “modern art”. Schaeffer claimed: “this new technique of fragmentation fits the world view of modern man… a fragmented world and fragmented man.” 14

It’s been said before the works of Pablo Picasso contain truth without logic – “like being inside a dream”. But can such a dichotomy exist in the real world? Just look around. Whether logic is added to lies or reason is subtracted from truth, the results are the same: Clownworld.

In the chapter titled “Modern Art, Music, Literature, and Films”, Schaeffer tracked what he termed “the absurdity of all things” into twentieth-century music, books, and cinema. He furthermore noted the “strange contrast to the airplanes in our airports or slicing through our skies”:

It’s been said before the works of Pablo Picasso contain truth without logic – “like being inside a dream”. But can such a dichotomy exist in the real world? Just look around. Whether logic is added to lies or reason is subtracted from truth, the results are the same: Clownworld.

In the chapter titled “Modern Art, Music, Literature, and Films”, Schaeffer tracked what he termed “the absurdity of all things” into twentieth-century music, books, and cinema. He furthermore noted the “strange contrast to the airplanes in our airports or slicing through our skies”:

An airplane is carefully formed; it is orderly (and many would also think it beautiful). This is in sharp contrast to the intellectualized art which states that the universe is chance. Why is the airplane carefully formed and orderly…? Simply because an airplane must fit the orderly flow lines of the universe if it is to fly! Sir Archibald Russell (1904-1995) was the British designer for the Concorde airliner. In a Newsweek: European Edition interview (February 16, 1976) he was asked: “Many people find that the Concorde is a work of art in its design. Did you consider its esthetic appearance when you were designing it?” His answer was, “When one designs an airplane, he must stay as close as possible to the laws of nature. You are really playing with the laws of nature and trying not to offend them. It so happens that our ideas of beauty are those of nature. Every shape and curve of the Concorde is arranged so it will conform with the natural flow as conditioned by the laws of nature.” – Schaeffer, “How Should We Then Live?”, page 196Just as twentieth-century theologians like C.S. Lewis and Augusto Del Noce defined “Scientism” as the totalitarian conception of science, in which science is regarded as the only true from of knowledge, Francis Schaeffer, in 1976, termed such myopia as “sociological science”. His contention was that modern modern science has no “epistemological base… for being sure that what scientists think they observe corresponds to what really exists.”15 He claimed once scientists abandoned the “Christian base”, they made the philosophy of positivism their base for knowing – but the data is subjectively processed through the senses of an observer and according to the bias of the scientists. This means there can be no certainty that scientific observation/data is “not just illusion”.16 This brought to my mind the final words of C.S. Lewis in his 1943 book “The Abolition of Man”… “to ‘see through’ all things is the same as not to see.” Schaeffer claimed humanists have no base for “knowing” within their own philosophic system and, thus, modern modern science tends to bifurcate into a “high form of technology, often with a goal of increasing affluence” or “sociological science”… whereby “with a weakened certainty about objectivity, people find it easier to come to whatever conclusions they desire for the sociological ends they wish to see attained.”15 In addition, Schaeffer noted how weakened objectivity in science also corresponded with the rise of a sociological media:

This [weakened objectivity] is parallel to a change among the news makers. As their concept of truth becomes more relative, the ideal of objectivity in the news columns in contrast to the editorial pages is increasingly diminished. Thus, the loss of a philosophic base for truth and the certainty of knowing has the practical result of making for a sociological science and a sociological news medium – both available for use by manipulators. And this is especially potent with science because of the almost “religious” belief which people have developed about the objectivity – and thus the certainty – of the results of science. – Schaeffer, “How Should We Then Live?”, page 200Bill Gates founded Microsoft in 1975, a year before ““How Should We Then Live?” was published. But Francis Schaeffer warned us about “manipulators” like Gates and the scientific fork-in-the road separating high forms of technology with the goal of increasing affluence and the psychological, even religious, acceptance of sociological science. The Gates-funded COVID-19 media manipulation comes to mind; and the correlative rigorous enforcement of arbitrary mandates. Or, in the words of the French philosopher Voltaire: “Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities“. According to Schaeffer:

Modern people, on their basis of reason, see themselves only as machines. But as they move into the area of non-reason and look for their optimism, they find themselves separated from reason and without any human or moral values. – Schaeffer, “How Should We Then Live?”, page 202Once again, Schaeffer echoed the predictions of C.S. Lewis. In the final analysis of “The Abolition of Man” (1943), Lewis predicted that a small group of wizards, in the pursuit of power, would perfect psychology and technology to the point they could create a new reality – but the wizards would not be human because they will have erased the age-old system of values that has always constrained humanity across all cultures. Consequently, Schaeffer identified Materialism as the philosophic base for Marxist-Leninism, and noted that it “gives no basis for the dignity or rights of man”. And yet people are attracted to Marxism “by its constant talk of idealism”. In this sense, according to Schaeffer, Marxist-Leninism is a Christian heresy, because Christianity actually does provide a base for the dignity of man.17 Once the Christian consensus died, Schaeffer identified some of the available alternatives and none of them were optimistic. Hedonism was one possibility, but a society built on hedonism leads to chaos. Another possibility is the “absoluteness of the 51-percent vote”:

In the days of a more Christian Culture, a lone individual with the Bible could judge and warn society, regardless of the majority vote, because there was an absolute by which to judge. There was an absolute for both morals and law. But to the extent that the Christian consensus is gone, this absolute is gone as a social force. – Schaeffer, “How Should We Then Live?”, page 223Besides the chaos of hedonism or the absoluteness of the 51-percent vote, Schaeffer believed there was only one other alternative left: “one man or an elite, giving authoritative arbitrary absolutes”; and this “simple but profound rule”: If there are no absolutes by which to judge society, then society is absolute. This is because “arbitrary absolutes can be handed down and there is no absolute by which to judge them”.18 It was Schaeffer’s contention that modern modern man destroyed “the base which gave him the possibility of freedoms without chaos” and, thus, Schaeffer saw two effects manifesting as a result of “our loss of meaning and values”: 1.) Societal degeneracy, decadence, depravity, and violence… and… 2.) Some elite group or person stepping up to offer “arbitrary absolutes” in order to save us from ourselves. As these manifestations progressed, Schaeffer questioned if men would stand to defend their liberties or, instead, give them up “step by step, inch by inch”; and he (quite accurately, in retrospect) predicted liberties would be forfeited by both young and old, alike, as long as their life-styles were not threatened.19

Manipulation and the New Elite

Similar to his twentieth-century philosophical peers, C.S. Lewis and Augusto Del Noce, Francis Schaeffer foresaw the “coming of an elite, an authoritarian state, to fill the vacuum left by the loss of Christian principles”.20 And, like Lewis and Del Noce, Schaeffer concluded it would not be our father’s (i.e. twentieth-century) form of communism or fascism:….we must not think naively of the models of Stalin and Hitler. We must think rather of a manipulative authoritarian government. Modern governments have forms of manipulations at their disposal with the world has never known before. – Schaeffer, “How Should We Then Live?”, page 228Augusto Del Noce wrote a similar assessment in the 1970’s (that was reprinted in the 2014 compilation of his earlier writings):

..All that people on the right do, essentially, is identify totalitarianism with Stalinism and deny that Communism might undergo a democratic evolution… People on the left evoke the ghost of a Fascist threat… and to some kind of ill-defined “American imperialism”… There are also centrists who want to oppose all forms of totalitarianism, both Communist and Fascist. What utterly escapes all three positions is the new totalitarian reality that is taking shape.” – Del Noce, Augusto. “The Crisis of Modernity”, trans. Carlo Lancellotti, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2014 , pgs. 95-96Francis Schaeffer additionally addressed technocratic totalitarianism by referencing methods and theories of manipulation, psychological techniques, biological science, and media influence; starting with Sigmund Freud’s psychological determinism, B.F. Skinner’s sociological determinism (through conditioning), and Francis Crick’s chemical/genetic determinism. At the same time, Schaeffer pointed out that researchers like Skinner, as an example, could not live “on the basis of his own system” and that he lived “inconsistently on the memory of Christian values for which his system has no place.”21 Certainly, if he were alive today, Schaeffer would vehemently disagree that humans are merely “hackable animals” as claimed by the modern secular humanist, and World Economic Forum adviser, Yuval Noah Harari. Unfortunately, however, Schaeffer did concede that modern determinism has yielded two practical results: First, people “have opened themselves to being treated as machines and treating other people as machines. And, secondly, every theory of determinism “has carried with it a method of [psychological, sociological, chemical] manipulation.22 Furthermore, now that “man no longer sees himself as qualitatively different from non-man” (i.e. a hackable animal), Schaeffer added: “on the basis of nature there is no way man can derive the ought from the is.” 23 And “once people accept this mentality, it is much easier to impose arbitrary absolutes.” 24 And that, it would appear, my friends, is how sh*t happens.

Just as Schaeffer identified sociological science, he also identified sociological law, and sociological news. He predicted an elite class would increasingly use mass media as a “grid” by which to present their world view. In so doing, they would utilize “news organizations, newspapers, news magazines, wire services, and news broadcasts that have the ability to generate news.” In short, these would become “news makers” so that whatever appears in them becomes the news.25

Schaeffer also foresaw the malevolent use of “high-speed computers”, ever-expanding “information storage”, and a “manipulative authoritarian government” coming “from the administrative side or from the legislative side”, or through what could become known as “the imperial judiciary” 26:

Just as Schaeffer identified sociological science, he also identified sociological law, and sociological news. He predicted an elite class would increasingly use mass media as a “grid” by which to present their world view. In so doing, they would utilize “news organizations, newspapers, news magazines, wire services, and news broadcasts that have the ability to generate news.” In short, these would become “news makers” so that whatever appears in them becomes the news.25

Schaeffer also foresaw the malevolent use of “high-speed computers”, ever-expanding “information storage”, and a “manipulative authoritarian government” coming “from the administrative side or from the legislative side”, or through what could become known as “the imperial judiciary” 26:

…As the memory of if the Christian consensus which gave us freedom within the biblical form increasingly is forgotten, a manipulating authoritarianism will tend to fill the vacuum. The central message of biblical Christianity is the possibility of men and women approaching God through the work of Christ. But the message also has secondary results, among them the unusual and wide freedoms which biblical Christianity gave to countries where it supplied the consensus. When these freedoms are separated from the Christian base, however, they become a force of destruction leading to chaos. When this happens, as it has today, then to quote [American moral and social philosopher] Eric Hoffer (1902-1983), “When freedom destroys order… the yearning for order will destroy freedom.” At that point, the words left or right will make no difference. They are only two roads to the same end. There is no difference between an authoritarian government from the right or the left: the results are the same. An elite, an authoritarianism as such, will gradually force form on society so that it will not go on to chaos. And most people will accept it – from the desire for personal peace and affluence, from apathy, and from the yearning for order to assure the functioning of some political system, business, and the affairs of daily life. – Schaeffer, “How Should We Then Live?”, page 245

How Should We Then Live?

Ironically, “How Should We Then Live?” was published in 1976… the very same year that I marched in a bicentennial parade and Peter Finch, playing Howard Beale, told us to shut off our televisions in the Oscar-nominated film “Network”. Yet, even back then, Francis Schaeffer predicted America’s future thusly: Economic collapse, war, societal violence / terrorism, global wealth redistribution, and shortages of food and natural resources:Overwhelming pressures are being brought to bear on people who have no absolutes, but only have the impoverished values of personal peace and prosperity. The pressures are progressively preparing modern people to accept a manipulative, authoritarian government. – Schaeffer, “How Should We Then Live?”, page 246Schaeffer also claimed the “men in Western Governments” did not understand that “freedom without chaos” was NOT a “magic formula” that could be imported to any nation. This is because “freedom without chaos” derived from a Christian base and it could not be separated from its roots.27 As a result, Schaeffer predicted a forthcoming “tyranny of the majority” in the United Nations and its chartered organizations, particularly, “in the midst of the winds of political change.” He claimed: “When the [Christian] principles are gone, there remains only expediency at any price.” 28 Schaeffer warned that freedom would disintegrate as “the memory of the Christian base” grew “ever dimmer”.28 And, eerily, it almost seems as if Schaeffer was envisioning the emergence of CBDCs, digital ID, and the proposed WHO pandemic treaty, when he asked this question:

Without the base for right and wrong, but only a concept of synthesis, pragmatism, and utilitarianism, what will not be given up, both inside of nations or in foreign affairs, for the sake of immediate peace and affluence? – Schaeffer, “How Should We Then Live?”, pages 251-252In Schaeffer’s last chapter, entitled “The Alternatives”, he quoted the Bible and, specifically, Paul the Apostle’s Letter to the Romans (chapter 1) – but without exactly identifying it as such. Instead he attributed the words as coming from a Jew who became a Christian writing to those in Rome; and citing the failure of Greek and Roman ideologies to perceive the uniqueness of man amid the existence and form of the universe. Personally, I found Schaeffer’s clarifications in the brackets (below) to be interesting from both a phenomenological and ontological perspective, respectively:

The retribution of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who suppress the truth in unrighteousness. Because that which is known of God is evident within them [that is, the uniqueness of man in contrast to non-man], for God made it evident to them. For the invisible things of him since the creation of the world are clearly seen, being perceived by the things that are made [that is, the existence of the universe and its form], even his eternal power and divinity; so that they are without excuse. – Schaeffer, “How Should We Then Live?”, page 253Addressing Christians directly, Schaeffer claimed “humanistic thinking” accepts the following dichotomy: The separation of [philosophical] optimism about meaning and values from reason. And, once this separation is accepted, whatever an individual inserts into the area of non-reason is “incidental”.29 According to Schaeffer:

… God exists… that he has not been silent but has spoken to people in the Bible and through Christ was the basis for the return to a more fully biblical Christianity in the days of the Reformers. It was a message of the possibility that people could return to God on the basis of the death of Christ alone. But with it came many other realities, including form and freedom in the culture and society built on that more biblical Christianity. The freedom brought forth was titanic, and yet, with the forms given in the Scripture, the freedoms did not lead to chaos. – Schaeffer, “How Should We Then Live?”, page 253At the beginning of “How Should We Then Live?”, Schaeffer contended that “no totalitarian authority nor authoritarian state can tolerate those who have an absolute by which to judge that state and its actions”. This is why, he claims, Christians were fed to wild beasts in Ancient Rome: “The Christians had that absolute in God’s revelation… an absolute universal standard by which to judge…”30 Then, at the close of his book, Schaeffer admonished Christians not to fall prey to humanistic thinking (which he also labels as existential methodology), and, instead, he advises to hold fast to “the value system, and the meaning system, and the ‘religious matters’ given in the Bible”. In so doing, the “real absolute” will be maintained “by which to help, or by which to judge, the culture, state, and society.” Furthermore, he exhorts Christians to know and “to act upon that world view so as to influence society in all its parts…” and to “resist authoritarian government in all its forms”. Accordingly, Schaeffer said the following statement was one to memorize: “To make no decision in regard to the growth of authoritarian government is already a decision for it.”31 And that concludes my review of the 1976 book “How Should We Then Live? The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture”, by Francis A. Schaeffer. What then will be decided? Isn’t that always the most important question?

References:

1. Schaeffer, Francis A.. “How Should We Then Live? The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture”, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1976 , page 17. 2. Ibid., page 19 3. Ibid., page 20 4. Ibid., pages 130-131 5. Ibid., page 132 6. Ibid., page 146 7. Ibid., pages 146-147 8. Ibid., page 147 9. Ibid., pages 162-163 10. Ibid., page 178 11. Ibid., page 182 12. Ibid., pages 182-183 13. Ibid., page 190 14. Ibid., pages 184-187 15. Ibid., pages 199-200 16. Ibid., pages 198-199 17. Ibid., page 215 18. Ibid., page 224 19. Ibid., pages 226-227 20. Ibid., page 228 21. Ibid., page 229 22. Ibid., page 230 23. Ibid., page 237 24. Ibid., page 238 25. Ibid., pages 242-243 26. Ibid., pages 244-245 27. Ibid., page 249 28. Ibid., page 250 29. Ibid., page 255 30. Ibid., page 26 31. Ibid., pages 256-257 Read more at: TheBurningPlatform.comFeds colluded with big banks to spy on Americans’ financial transactions

By News Editors // Share

University of Virginia spends $20 million on 235 DEI employees, with some making $587,340 per year

By News Editors // Share

Boeing whistleblower found dead in a truck from “self-inflicted gunshot wound”

By News Editors // Share

Israel coerced UN agency for Palestinian refugees into LYING about Hamas links

By Ethan Huff // Share

Nicotine Unveiled: A misunderstood molecule demonized by Big Pharma

By ramontomeydw // Share

Judges rule 4,400+ times that Trump administration illegally detained immigrants

By lauraharris // Share

U.S. imports from Taiwan surpass goods from China for the first time in decades

By lauraharris // Share

Nighttime beverages: How your choice of drink shapes sleep quality

By dominguez // Share